As a writer, you’re conditioned to expect that you won’t make much money. This is probably wise, given that you’re unlikely to see a lot of it. While a rare few of us are Scrooge McDucking it, it’s important to recognise that these writers are breathing rare air and you’ll be lucky to ever get a passing whiff of it.

While some of us can make a reasonable living wage from our words, most of us, if forced to survive solely on our writing income, would find that it offers an opportunity to learn the true meaning of the word penury. Book sales alone are unlikely to see you afford the kind of life I once dreamed of as a writer, where I could write a book then spend the next decade living off the proceeds while I stared out of the window and thought about the next one. The average annual writer salary has notably dropped in recent years to around £7k, and some of us consider ourselves fortunate to get even that. You can accuse writers of a lot of things, but only being in it for the money isn’t one of them*. Still, that doesn’t mean we should lose sight of the fact that our time and effort has value. Especially when time and effort is increasingly something that publishing wants more of from you.

It’s no longer enough to simply write a book. Although it feels like the end result, it’s actually just the start. While your publisher will offer a degree of help with marketing and publicity, a lot of it is on you. In the run up to publication your job becomes less that of a writer and more one of a town crier. You must take to your socials and ring that bell, overcoming any squeamishness about self promotion to yell your book title, its blurb and the places it can be pre-ordered from because PRE-ORDERS COUNT AS FIRST WEEK SALES AND INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF HITTING THE TIMES BESTSELLER LIST. And unless you want your book to vanish without a trace, you must keep this up until you publish the next one and so on and so on until either you or the appetite for your books expires.

Self marketing is an important part of selling your book and, to that end, most publishing contracts now include clauses where the author has to agree to a certain amount of promotion. You’ll be asked to issue a number of social media posts within a specified timeframe, write articles for publications and appear at book events, all in the name of piquing someone’s interest and convincing them to buy your book. The details can all be negotiated, but broadly you’re asked to pitch in and will likely have to agree to some of it. It’s a lot for many of us, being asked to step blinking into the spotlight when we’ve spent the preceding period in a solitary state, staring into a screen and tapping a keyboard while eating biscuits. But, you must remind yourself, there are biscuits on tour. Especially if, like me, you’ve written a book with biscuits in the title.

What you must keep in mind though is that, unless your book tour includes festival dates or your publisher has deep enough pockets to set aside funds for it, you are unlikely to be paid for any of the time and effort this eats up. The same goes for writing articles, many of which you’re expected to work on gratis. I have written for publications that paid me well and others that paid me nothing. You should take these offers on a case by case basis but when they result in a story about your genitals being presented to a global audience (see Metro screenshot below), I guess they can be considered priceless**.

Ultimately, that Metro piece sold books, and whether or not an article will do this is the primary question you need to ask yourself when weighing up unpaid writing opportunities. If the answer is likely yes and it’s not going to take up too much of your valuable time, then it’s worth a punt. Unless you’ve been asked to write about a subject you were already dying to discuss, that financial calculation is vital because free work is consuming time that you could be using to do, and be paid for, something else. Or even just enjoying your life and not thinking about commodification, which is important too. That ‘staring out of the window’ thing is always a valid option.

When it comes to being offered a festival appearance, you have to ask yourself a few additional questions. Chief among them is who else, if at all, is getting paid to be there. Some festivals are small, staffed entirely by volunteers and no one involved is being paid for their efforts. They’re just in it for the love of it. If I like the sound of a festival and its ethos and don’t have to travel too far to be there then I’ll agree to not be paid either, in exchange for the chance to sell some books and meet readers. Most festivals will pay though, even the small ones. Some are egalitarian enough to offer the same fee whether you’re Margaret Atwood or an unknown but with others its more of a negotiation. Most often the amount you get does not exceed £250 but I’ve received the occasional £300 or £500. When possible, I’ve donated my fee to smaller festivals, which is nice to do whenever you can afford it but you should never feel obliged to. If you do though, remember that you can write off your travel and food expenses against tax, which can be calculated by an accountant whose fees, I was delighted to learn, are also a valid tax deduction. The question then really comes down to the cost of your time.

I recently turned down a festival appearance that would have involved a round trip of close to 7 hours and would not include a fee. There were other big/TV famous writers on the festival lineup, whom I had to assume were being paid, but I don’t get bent out of shape about other people’s financial arrangements as long as the opportunity is a good one for me. It was not. While the event was interesting, it was planned too late in the day to be included in the festival programme, so most people wouldn’t know it was happening. There would be an opportunity to sell books afterwards, I was told, but as few people knew it was happening, it fell down on basic economics. It was not worth my time, so I said ‘thank you, but no thank you.’

I’d initially felt good about myself for this. I had confirmed my value, even if all I’d confirmed was that this value was upwards of zero. Still, it took a while for me to shake the sense that I’d done something wrong. That I’d let people down by refusing an opportunity. It seemed rude of me. As someone who actually enjoys being dragged away from my computer and shoved into the spotlight, meeting and connecting with readers is my favourite part of being a writer, so to refuse an opportunity to do that felt transgressive somehow. I’d felt a similar way when I turned down the offer of a three page spread in a major publication because the angle they wanted to take was, to my sensibilities, gross and weird***. I double checked it with a few writer friends who all agreed it was a bad move. Still, I felt bad for turning down the offer of work and promotion that would have placed me and my book in front of close to a million potential readers. This could have led to a higher profile, more events and even more opportunities to meet readers. Instead, I said no and felt bad about it for months.

Where I think this comes from is a working class understanding that jobs are precious and offers of them can disappear in an instant. Someone else will take that work if you don’t want it, and the folks who offered it to you are not likely to ask you again. Discouraging future offers of unpaid labour should feel great but instead it can feel like you’re turning down the last chance you’re ever going to get. In these moments, I’m reminded of my dad who, at almost 70 and in increasingly ill health, was still working 12 hour shifts as a gas terminal engineer because he couldn’t bring himself to pass up the work. When I asked him why he said, almost desperate in his exhaustion, “They keep offering me shifts!” What I was being offered was exposure, which, as the old saying goes, we can’t live off but we can die from.

What I need to remind myself during these decision moments is the thing I often say to other writers; your time and effort has value, one that decreases if you say yes to everything. Its worth is only as great as the price tag you stick on it. You should absolutely say yes to as many things as possible because you never know what they can lead to, but don’t say yes to everything, especially if it instinctively feels wrong. You and your readers will find each other in time and you’ll appreciate that so much more if you haven’t had to sell your soul and brand yourself as worthless in order to make that happen.

*There are plenty of celebrity authors who are only in it for the money but as only a few of them actually write their own books, I think I’m on pretty solid ground with this statement.

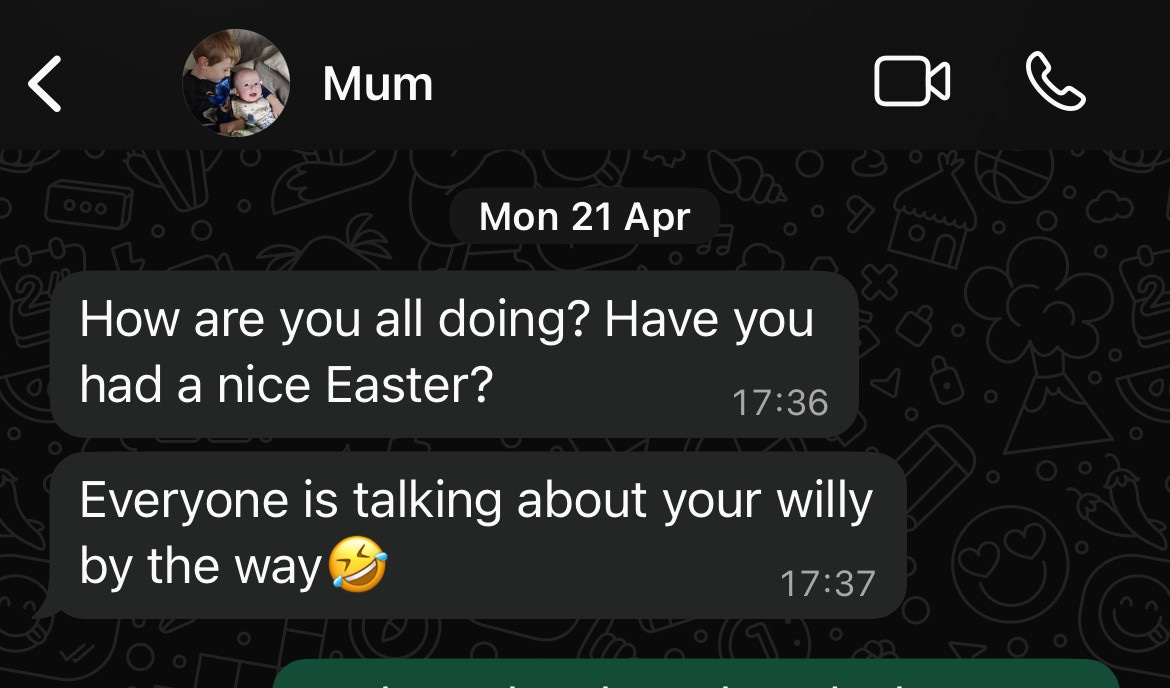

**For a good day or so, this story was No.1 in Metro’s Sex chart. It also resulted in this frameable WhatsApp from my mum.

***If you want to know what it was about, come to one of my events and ask me. I’ll tell you everything.

Any other business:

What I’m Reading: The Art Thief by Michael Finkel. A stunning, novelistic work of nonfiction about the daring art thief Stéphane Breitwieser. AI art thieves could never hope to inspire a book as wondrous as this. On that subject, I’ve also been listening to the audiobook of Laura Bates’ incredible but terrifying The New Age of Sexism: How the AI Revolution is Reinventing Misogyny. It should be required reading for all, but especially men. Put it on the national syllabus.

What I’ve been listening to: Billionaire by Kathleen Edwards. She is exceptional and I’ve adored her since stumbling over her songs on Last.fm about 20 years ago. She frequently moves me to tears and the title track of this new album, about dealing with the loss of a beloved friend, absolutely floored me. I’ve been listening to it on a loop.

What I’ve been doing: On the surface, nothing. In actual fact, I’ve been doing my full time day job that has nothing to do with writing while planning upcoming literature events, writing articles (paid and unpaid), reading several manuscripts to provide quotes, researching for my next essay collection and preparing a lecture, occasionally stopping to wonder when (not if) my brain will snap.

What I’ll be doing: I’ll be at the Chorlton Book Festival on September 16th in the newly refurbished Chorlton library chatting about Broken Biscuits and Other Male Failures with the author Steve Kedie. On October 16th I’ll be at Serenity Booksellers in Stockport chatting to Graham Robb about his new biography The Discovery of Britain. Then, on the 18th, I’ll be at the Ilkley Literature Festival recording a live episode of The Working Class Library podcast, where we’ll be discussing Alan Bennett’s Untold Stories. On November 20th I’ll be one of the speakers at Berwins Salon North in The Crown Hotel, Harrogate, talking about the unifying power of embarrassing stories, recreating a mortifying incident from my teens and playing a game of ‘Would You Rather?’ involving a Cringe-o-meter. You can also now book places on the narrative nonfiction course I’m running at The Ted Hughes Arvon Centre, Lumb Bank from February 2nd to the 7th 2026 alongside the excellent Miranda France and Catherine Taylor.

The one-man marketing team, it’s fair to say, is not the aspect of ‘being a writer’ that most of us think of when we aspire to it :-) Funnily enough the latest Tom Cox newsletter (he has just moved off Substack) mentioned his guilt at having to miss some events and the opportunity to sign a load of books due to being ill in a ‘visits to A&E’ sense. It’s a lot of pressure, which I can’t help thinking discriminates against disabled writers.

By the way - footnotes. Apologies if it’s a stylistic choice, but in case it’s just you being new to Substack, there’s an actual footnote option so that the reader can click on or hover over the number and it shows the text, without having to scroll to the end then find your place again. I know this because I overuse them.

Very illuminating, very true . The working class thing chimed . Town crier and mum message made me chortle.

Thank you 😊